Last Updated on October 24, 2021

Table of Contents

In an interesting document, Managing complexity (and chaos) in times of crisis. A field guide for decision makers inspired by the Cynefin framework created by Dave Snowden and Alessandro Rancati for the Joint Research Centre (JRC), the EU Science Hub, the authors present a “field guide” to “navigate crises using the Cynefin framework as a compass.” Following are my 2c about some of the issues I have with some statements in this paper. I have to make clear that I think the document is an excellent primer for process improvement, but I’m not sure if it can be as useful as a “field guide” for managing a crisis.

I was expecting to find in the document some practical “rules of engagement” for how to manage complexity in a time of crisis, but the authors primary interest seems to be, not to deal with (manage) the crisis in order to, minimize losses, and preserve as much as possible of the organization, but rather to use the crisis as an opportunity for the implementation of (lasting?) organizational changes:

During moments of stability, when bureaucracy and conservative interests tend to grow in importance, organisations evolve into a deeply entangled complex system, like bramble bushes in a thicket or the root system of a mangrove swamp. In a crisis, much of this entanglement can and should be surrendered to the moment There is a real chance to sense, see and actuate new forms of simplicity to increase the overall agility and resilience of the organisation.

Chaos places us in a very fluid context: first we have to gain some form of control, then we need to empower informal networks through light organisational structures. Resources need to be radically and, possibly, permanently reallocated. Life is not going to be the same again, even if we escape unscathed from the situation. We can’t predict outcomes, so we need to shift and move at speed and be open to new possibilities on the journey; manage the risk as well as the possibilities. The only thing we know for certain is that there will be unintended consequences: we must be prepared for those too.

Crisis as a Trigger for Change

Using a crisis as a reason for change seems like a good idea at first, because a crisis-induced “chaos” is, as B. Radej nicely put it in “Cynefin hits again“, “a blessed place where old rules fall apart while new ones are not jet available“, so the scared bureaucrats might in such situations be more open to accepting change than when things are “normal” and they feel more in control.

However, to follow the original “gardening” analogy, to start cutting through the bramble bushes in a thicket during the storm may not be a good idea. I believe it is very unlikely that measures implemented in a “fluid” crisis situation, that were necessary to keep the organization afloat on the whitewater of chaos, will be preserved after the situation calms down.

If we accept that every radical organizational change has some characteristics of an “insurgency”, Thomas Sowell’s words of caution from his book Knowledge and Decisions sound appropriate:

“… the kinds of people attracted to the original insurgency, under the initial set of incentives and constraints, tend to be very different from the kinds of people who gravitate to it after it has become successful and achieved a major part of its goals. By definition, an insurgent movement forms under a set of incentives and constraints very different from those which it seeks to create.”

Informal Networks

It is ultimately the people who remain in the organization after the crisis that will have to maintain (or not) whichever measures were implemented while dealing with the crisis. In their “field guide” Snowden and Rancati identify the need to “empower informal networks through light organisational structures” which, I think, means we have to recognize and make use of those people on the fringes of the organization that constantly “bend established rules” just to keep things going. Unfortunately, these people don’t have too much use (or respect) for formal organizational structures because they are often under the constant peril of being vilified as “troublemakers” when things are (apparently) good for everyone else.

While these kinds of people with their creativity and ingenuity can for sure be a great asset in dealing with a crisis, the problem is that, in order for this to work, informal networks have to be already established in the organization. Such informal networks are based on trust and evolve over long periods of time. Any attempt to create them artificially or by “fiat” in the middle of a crisis, by introducing a “breakfast” or some other kind of “informal” meeting, is likely to fail miserably. In order for these “light organisational structures” to be useful in a moment of crisis, they must be recognized and given a proper place in the organization before the crisis. Standard organizational policies and procedures should recognize, document, and facilitate the use of informal “best practices” already in place in the organization, not force the use of some processes just because they are mandated from “above” or part of one or another manager’s pet project.

Human “resources”

The other suggestion in the document is about a “radical reallocation of resources” and has pitfalls of its own. I assume that under the term “resources” the authors also include “human resources”. Throwing more money (if available) at weak spots in the organization may not help much in a crisis, but it won’t do any harm either. For the people of the organization, however, being in a state of crisis means a lot of uncertainty. Sudden “radical” reallocation of people (reorganization) may add to that feeling of helplessness. What the organization needs the most in a crisis is stability and some assurance that everything will be well in the end.

Conclusion

So, at the end of this rant, here are just a few reasons that pop in mind why organizational changes during a crisis may, in my opinion, not be the best strategy:

- A crisis is not a good moment for starting organizational changes because it is adding to the already present uncertainty. It is better if changes are implemented in “quieter” periods and a crisis situation is then used for the validation and to find weak spots in the organization’s processes.

- The goals for all organizational changes is to increase it “fitness” to deal with the ever changing environment. This includes increasing the efficiency of the work in its primary domain (developing products or delivering services), but must also address resilience to unpredictable disruptive situations or a crisis. Fortunately, the best solutions implemented for the former may be also useful for the later. A resilient organization should already have all the processes and procedures in place that provide the ability to detect (or even predict), analyze and manage crisis situations.

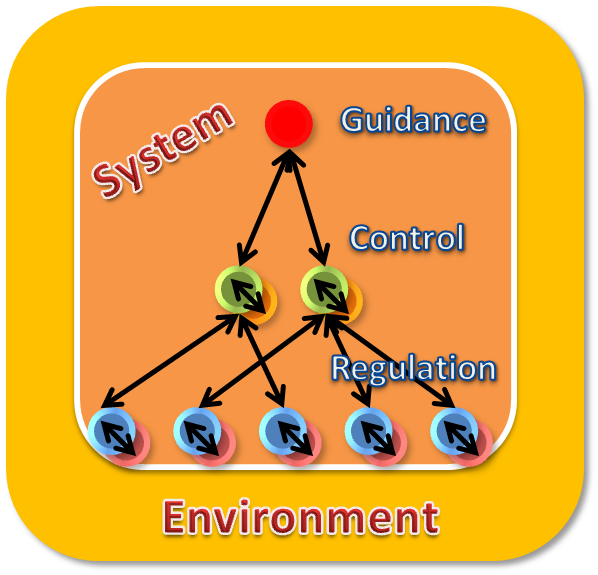

- It is normal, and should be expected that, in moments of crisis, a rigid, top-down, bureaucratic structure crumble under the pressure of uncertainty, but this was not the best organizational structure to begin with. Using lean and agile, supporting (control) structures as a matter of organizational principle becomes then of paramount importance in both “normal” and crisis situations.

- Resilience is achieved by implementing diversity and autonomy at the regulation level

- Optimization is implemented at the control level as a supporting, planning and resource leveling function, while

- Trying to predict the future and what may be the “next important thing” is then the only purpose of guidance

Here is the reaction from one of the authors to my rambling in this post:

Feature photo by Loren Dosti on Unsplash